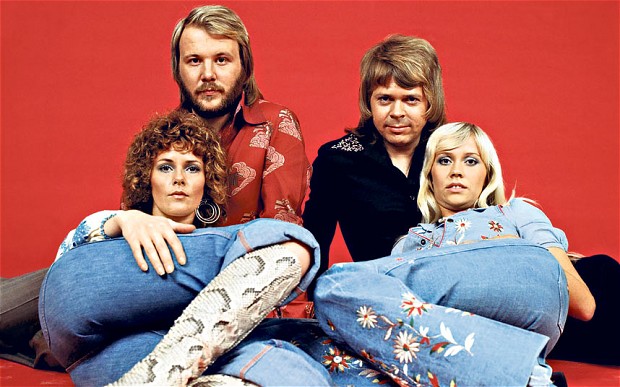

The Scandinavian midas touch

Decades before the rise of today’s Western and K-Pop hits, a Swedish quartet won hearts the world over with their brand of feel-good music. ABBA, consisting of Agnetha Fältskog, Björn Ulvaeus, Benny Andersson, and Anni-Frid Lyngstad, emerged from Stockholm as one of the most successful music groups of all time. Their hits “Mamma Mia!” and “Dancing Queen” are still popular today, thirty years after the group disbanded in the 1980s.

The Swedish are still music powerhouses, nurturing the likes of singers Robyn and Lykke Li. These days, however, the backstage mechanics of music production are where they truly shine. Increasingly, Sweden and its Scandinavian neighbours have muscled into a profitable niche — that of lending their music-making expertise to other singers.

This essay seeks to examine the role Scandinavian musicians play in the K-Pop industry. Like the K-Pop idols they write for, they were headhunted by Korean record labels after the latter was wowed by their track record in Western markets. The essay will chart the factors leading to their rise and establish their role as a proxy for East-West cultural flows.

How the Scandinavian pop machine works

Singaporean songwriter Tat Tong used the term “the Scandinavian pop machine” to refer collectively to European musicians who craft K-Pop songs for Korean record labels. They are especially in demand by the big three (SM, JYP, and YG). These songwriters and music producers hail mostly from Sweden and Norway, and the work they do is typically behind-the-scenes.

Despite its low profile, the prominence of the Scandinavian pop machine in the K-Pop industry is undisputed. They are the reliable hit-makers many K-Pop idols such as Girl’s Generation or BoA turn to. For example, Girl’s Generation’s “Tell Me Your Wish (Genie)”, which was written by Norway-based DSign Music, topped 10 different music charts within a few days of its release (MyDaily, 2009).

How differences are sorted out

The close professional links between Scandinavian songwriters and South Korea may seem strange considering that they hail from different parts of the world. Besides language and cultural barriers, Scandinavian musicians have to overcome geographical differences as they are mostly based in Europe rather than South Korea.

However, Korean companies decided that recruiting them was worth the effort due to their proven track record. Sweden in particular has a strong foothold in the U.S. music industry, the largest and most lucrative with a US$5 billion market value in 2012 (Recording Industry Association of Japan, 2013). Since the mid-1990s, for example, Swedish music producer Max Martin has scored 17 Billboard number one hits. These include “I Want It That Way” by the Backstreet Boys and “Baby One More Time” by Britney Spears. The South Koreans were quick to notice. SM Entertainment employees approached Pelle Lidell, a European executive from Universal Music Publishing, and bought 10 of his songs right away, including “Tell Me Your Wish (Genie)” (Russell, 2012).

To overcome language issues, Scandinavian musicians and their Korean clients rely on standardised work flows. Firstly, the Scandinavian musicians publish demos and send them to Korean entertainment companies. After the Korean company then selects a song, it instructs the music publisher to send over the instrumental version, without vocals. The Korean company then adds in the lyrics and vocals themselves (Oh, 2011).

It helps that K-Pop is easier for Scandinavian songwriters to get the hang of, as it is heavily influenced by global music styles (Russell, 2012). As early as the 1990s, Korean pop musicians incorporated American music genres like rap, rock and techno in their music (Laurens, 2006). K-Pop has been described by the Rolling Stones as "a mixture of trendy Western music and high-energy Japanese pop (J-Pop), which preys on listeners' heads with repeated hooks, sometimes in English.” (Benjamin, 2002).

It helps that K-Pop is easier for Scandinavian songwriters to get the hang of, as it is heavily influenced by global music styles (Russell, 2012). As early as the 1990s, Korean pop musicians incorporated American music genres like rap, rock and techno in their music (Laurens, 2006). K-Pop has been described by the Rolling Stones as "a mixture of trendy Western music and high-energy Japanese pop (J-Pop), which preys on listeners' heads with repeated hooks, sometimes in English.” (Benjamin, 2002).

Scandinavian competence

As the popularity of ABBA and Max Martin indicate, the Scandinavian pop machine was able to gain global acclaim as it was competent in its own right. Sweden, in particular, puts comprehensive policies in place to support its musicians.

Lee (2012) put forth three reasons for Sweden’s competitiveness. Firstly, there exists an atmosphere of cooperation rather than rivalry among musicians, as they can earn a decent pay at numerous schools and music academies. Secondly, the government supports Swedish music by funding 10 per cent of popular music, and by organising campaigns such as “Export Music Sweden”. Thirdly, the Swedish receive a high level of music education. Not only does the syllabus teach songwriting, it includes popular music genres such as pop and rock.

As the popularity of ABBA and Max Martin indicate, the Scandinavian pop machine was able to gain global acclaim as it was competent in its own right. Sweden, in particular, puts comprehensive policies in place to support its musicians.

Lee (2012) put forth three reasons for Sweden’s competitiveness. Firstly, there exists an atmosphere of cooperation rather than rivalry among musicians, as they can earn a decent pay at numerous schools and music academies. Secondly, the government supports Swedish music by funding 10 per cent of popular music, and by organising campaigns such as “Export Music Sweden”. Thirdly, the Swedish receive a high level of music education. Not only does the syllabus teach songwriting, it includes popular music genres such as pop and rock.

Apart from national policies, region-wide song contests such as Eurovision lend a platform for budding musicians to be heard.

Outreach efforts

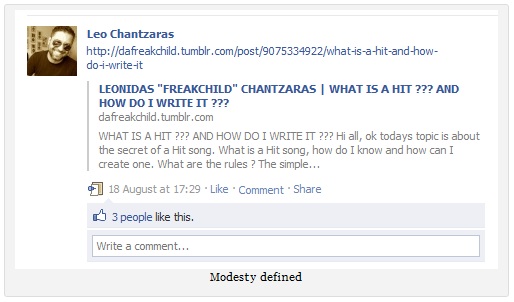

Although the Scandinavian pop machine plays a largely backstage role, it maintains a vibrant online presence. Songwriters can find avenues for creative expression, or post suggestions to help one another out. One such community is the 2,000-strong Facebook group “YES I SAID IT! The realities of being a songwriter”, where professional and budding songwriters, including Scandinavian musicians, share songwriting tips, videos, and events.

Within these groups, members play different roles. Some comment but do not post, while others contribute actively. For example, “YES I SAID IT! The realities of being a songwriter” is helmed by Mr Leonidas Chantzaras, a multi-gold and platinum songwriter signed on to BMG Rights (DaFreakchild Website, 2014). He is the big brother of the group, with posts such as: “The main message I wanna get out there for new writers who feel kind of lost and think that it s not possible to step into this business, is this.. I am living proof that you can reach it all.”

Outreach efforts

Although the Scandinavian pop machine plays a largely backstage role, it maintains a vibrant online presence. Songwriters can find avenues for creative expression, or post suggestions to help one another out. One such community is the 2,000-strong Facebook group “YES I SAID IT! The realities of being a songwriter”, where professional and budding songwriters, including Scandinavian musicians, share songwriting tips, videos, and events.

Within these groups, members play different roles. Some comment but do not post, while others contribute actively. For example, “YES I SAID IT! The realities of being a songwriter” is helmed by Mr Leonidas Chantzaras, a multi-gold and platinum songwriter signed on to BMG Rights (DaFreakchild Website, 2014). He is the big brother of the group, with posts such as: “The main message I wanna get out there for new writers who feel kind of lost and think that it s not possible to step into this business, is this.. I am living proof that you can reach it all.”

Besides their fellow musicians, Scandinavian songwriters also reach out actively to K-Pop fans. This is a strategic move, given that fan groups are one of the largest consumers of K-Pop music. In 2013, DSign Music granted an exclusive interview to Girl’s Generation fan site Soshified, in which they revealed their work with the group.

Bi-directionality of cultural flows

Globalisation in music is exemplified by both the Scandinavian pop machine and the K-Pop industry. Each has cultivated extensive ties with music markets worldwide, and both continue to do so. Korean record labels are not the first clients of Scandinavian songwriters, who cut their teeth working for the U.S. music industry. Neither are Korean companies entirely dependent on the Scandinavian pop machine. SM Entertainment sources music from around the world, including the U.S and Japan. It even worked with American songwriter Teddy Riley to lend “The Boys” by Girl’s Generation an urban American flair.

It appears that both parties mutually rely on each other. Although the Scandinavian pop machine has been headhunted to write for Korean companies, the reverse is also true. European musicians are keen to work with South Korea as it pays well in royalties, according to Mr Lidell (Lindvall, 2011). Moreover, they are well compensated. DSign Music makes “hundreds of thousands of pounds from K-Pop each year.” (Lindvall, 2011).

However, the directionality of cultural flows is a matter of debate. While K-Pop has retained its national identity with Korean singers and lyrics, its music style is more in line with the tastes of global audiences, having drawn on Western templates. K-Pop has been described by Ono and Kwon (2013) as a “hybrid colonial form that both worlds and “unworlds” culture” (p. 200), where “worlding” refers to the transfer of First World culture into Third World contexts (Spivak, 1985).

Still, I would argue that K-Pop is an implicit “worlding” of First World culture, albeit one framed in the Korean context. In order to raise its global appeal, the K-Pop industry subscribes to the Scandinavian pop machine and follows norms dictated by in the West on how music should sound. In this way, it is part of the “worlding” described by Spivak (1985).

Conclusion: a return to roots

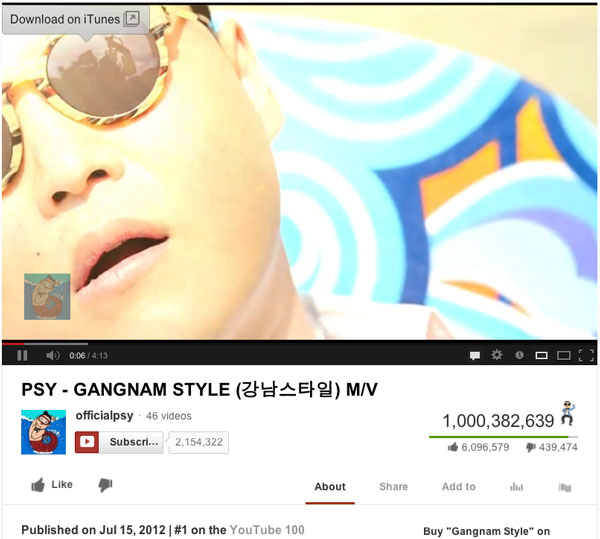

Ironically, while K-Pop is adopting Western influences to capture the market there, Western fans appear to be returning to an emphasis on authentic musical expression rather than tunes manufactured by specialised hit-makers. While teenage idols such as Justin Bieber are still popular, musicians who appear authentic, such as Adele, Lorde, and Taylor Swift, are often more well-received. Mr Tong noted that even Korean singer Psy, who is not a product of the K-Pop industry, won overwhelming success in the U.S. with his satirical hit, “Gangnam Style”.

Ironically, while K-Pop is adopting Western influences to capture the market there, Western fans appear to be returning to an emphasis on authentic musical expression rather than tunes manufactured by specialised hit-makers. While teenage idols such as Justin Bieber are still popular, musicians who appear authentic, such as Adele, Lorde, and Taylor Swift, are often more well-received. Mr Tong noted that even Korean singer Psy, who is not a product of the K-Pop industry, won overwhelming success in the U.S. with his satirical hit, “Gangnam Style”.

It would be interesting to see if the K-Pop industry will shift in this direction over time. Although the Scandinavian pop machine has helped lend it a sophisticated image, it has been criticised for lacking authenticity (Gabrielle, 2013; Johnson, 2013). Already, there is some indication that K-Pop music is coming into its own. Other than Psy, artistes such as Crayon Pop are gaining fame for their quirky songs, such as “Bar Bar Bar”. In this way, the ability of K-Pop to pull off a cool yet lovable image points to its dynamism and adaptability.

END

References

Benjamin, J. (2002, August 15). The 10 K-Pop groups most likely to break in America. Rolling Stone.

DaFreakchild Website (2014, February 13). THE STORE! Studio: Flavors.me. Retrieved from http://www.dafreakchild.com/

Gabrielle (2013, August 27). Is There Any "Art" Left in K-pop? - seoulbeats | seoulbeats. Retrieved from http://seoulbeats.com/2013/08/art-left-k-pop/

Johnson, J. (2013, January 15). the mind reels - On commercialization & authenticity in J-Pop & K-Pop. Retrieved from

http://blog.mjohnso.com/post/40653212190/on-commercialization-authenticity-in-j-pop-k-pop

Laurens, J. H. (2006). Musical terms worldwide: a companion for the musical explorer. Semar Publishers.

Lee (2012, October 11). Swedish music lessons for K-pop. JoongAng Daily. Retrieved from http://koreajoongangdaily.joins.com/news/article/Article.aspx?aid=2960615

Lindvall, H. (2011, April 20). Behind the music: What is K-Pop and why are the Swedish getting involved? The Guardian. Retrieved from

http://www.theguardian.com/music/musicblog/2011/apr/20/k-pop-sweden-pelle-lidell

Oh, J. (2011, March 3). Behind the scenes of East-West collaborations. The Korea Herald.

Ono, K. A., & Kwon, J. (2013). Re-worlding culture?. The Korean Wave: Korean Media Go Global, 199.

Recording Industry Association of Japan (2013). RIAJ yearbook 2013: IFPI 2011, 2012 report: 29. Global sales of recorded music (Page 24).

Russell, M. (2012, October 11). A Swede Makes K-Pop Waves. The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved from http://online.wsj.com/news/articles/SB10000872396390443982904578043852214588998

Soshified.com (2013, March 23). Behind Girls’ Generation’s hits: exclusive interview with Dsign Music. Retrieved from

http://www.soshified.com/2013/03/behind-girls-generations-hits-exclusive-interview-with-dsign-music

Spivak, G. C. (1985). Three women's texts and a critique of imperialism. Critical Inquiry, 243-261.

SportsKhan (2009, July 1). Girls' Generation' tops all digital charts, "All Kill" again. Retrieved March 12, 2014, from

http://sports.khan.co.kr/news/sk_index.html?cat=view&art_id=200907011938573&sec_id=540301&sk_id=08

Benjamin, J. (2002, August 15). The 10 K-Pop groups most likely to break in America. Rolling Stone.

DaFreakchild Website (2014, February 13). THE STORE! Studio: Flavors.me. Retrieved from http://www.dafreakchild.com/

Gabrielle (2013, August 27). Is There Any "Art" Left in K-pop? - seoulbeats | seoulbeats. Retrieved from http://seoulbeats.com/2013/08/art-left-k-pop/

Johnson, J. (2013, January 15). the mind reels - On commercialization & authenticity in J-Pop & K-Pop. Retrieved from

http://blog.mjohnso.com/post/40653212190/on-commercialization-authenticity-in-j-pop-k-pop

Laurens, J. H. (2006). Musical terms worldwide: a companion for the musical explorer. Semar Publishers.

Lee (2012, October 11). Swedish music lessons for K-pop. JoongAng Daily. Retrieved from http://koreajoongangdaily.joins.com/news/article/Article.aspx?aid=2960615

Lindvall, H. (2011, April 20). Behind the music: What is K-Pop and why are the Swedish getting involved? The Guardian. Retrieved from

http://www.theguardian.com/music/musicblog/2011/apr/20/k-pop-sweden-pelle-lidell

Oh, J. (2011, March 3). Behind the scenes of East-West collaborations. The Korea Herald.

Ono, K. A., & Kwon, J. (2013). Re-worlding culture?. The Korean Wave: Korean Media Go Global, 199.

Recording Industry Association of Japan (2013). RIAJ yearbook 2013: IFPI 2011, 2012 report: 29. Global sales of recorded music (Page 24).

Russell, M. (2012, October 11). A Swede Makes K-Pop Waves. The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved from http://online.wsj.com/news/articles/SB10000872396390443982904578043852214588998

Soshified.com (2013, March 23). Behind Girls’ Generation’s hits: exclusive interview with Dsign Music. Retrieved from

http://www.soshified.com/2013/03/behind-girls-generations-hits-exclusive-interview-with-dsign-music

Spivak, G. C. (1985). Three women's texts and a critique of imperialism. Critical Inquiry, 243-261.

SportsKhan (2009, July 1). Girls' Generation' tops all digital charts, "All Kill" again. Retrieved March 12, 2014, from

http://sports.khan.co.kr/news/sk_index.html?cat=view&art_id=200907011938573&sec_id=540301&sk_id=08